# HIDDEN

# Clear previously defined variables

%reset -f

# Set directory for data loading to work properly

import os

os.chdir(os.path.expanduser('~/notebooks/05'))

# HIDDEN

import warnings

# Ignore numpy dtype warnings. These warnings are caused by an interaction

# between numpy and Cython and can be safely ignored.

# Reference: https://stackoverflow.com/a/40846742

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore", message="numpy.dtype size changed")

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore", message="numpy.ufunc size changed")

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

%matplotlib inline

import ipywidgets as widgets

from ipywidgets import interact, interactive, fixed, interact_manual

import nbinteract as nbi

sns.set()

sns.set_context('talk')

np.set_printoptions(threshold=20, precision=2, suppress=True)

pd.options.display.max_rows = 7

pd.options.display.max_columns = 8

pd.set_option('precision', 2)

# This option stops scientific notation for pandas

# pd.set_option('display.float_format', '{:.2f}'.format)

Faithfulness¶

We describe a dataset as "faithful" if we believe it accurately captures reality. Typically, untrustworthy datasets contain:

Unrealistic or incorrect values

For example, dates in the future, locations that don't exist, negative counts, or large outliers.

Violations of obvious dependencies

For example, age and birthday for individuals don't match.

Hand-entered data

As we have seen, these are typically filled with spelling errors and inconsistencies.

Clear signs of data falsification

For example, repeated names, fake looking email addresses, or repeated use of uncommon names or fields.

Notice the many similarities to data cleaning. As we have mentioned, we often go back and forth between data cleaning and EDA, especially when determining data faithfulness. For example, visualizations often help us identify strange entries in the data.

calls = pd.read_csv('data/calls.csv')

calls.head()

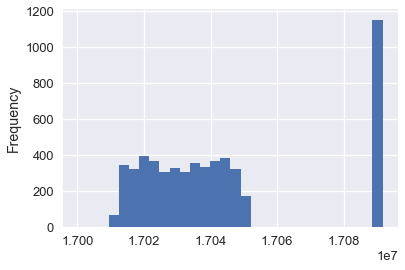

calls['CASENO'].plot.hist(bins=30)

Notice the unexpected clusters at 17030000 and 17090000. By plotting the distribution of case numbers, we can quickly see anomalies in the data. In this case, we might guess that two different teams of police use different sets of case numbers for their calls.

Exploring the data often reveals anomalies; if fixable, we can then apply data cleaning techniques.